Behind the Scenes: Building Real-Time Route Tracking for Indoor Climbing

code database ransac graphs affine

Indoor climbing gyms are constantly changing. Routes are reset, holds are moved, and entire walls can look completely different from one week to the next. Any system that tries to track climbs in this environment has to deal with one big challenge: the data is always in motion.

From the start, Ascendit was built around that reality.

Instead of relying on static route lists or manual selection, Ascendit takes a camera-first approach. Climbers scan the wall, confirm the route they climbed, and the app handles the rest. This keeps logging fast and ties every entry directly to what is physically on the wall, not what someone typed into a database weeks ago.

But turning a photo into a shared climbing project is not a simple image comparison problem.

When a scan is uploaded, it goes through a computer vision pipeline that detects individual holds and estimates their positions and sizes. These detected holds form a geometric fingerprint of the route, but that fingerprint has to be matched against existing projects taken from different angles, under different lighting, and often with missing or occluded holds.

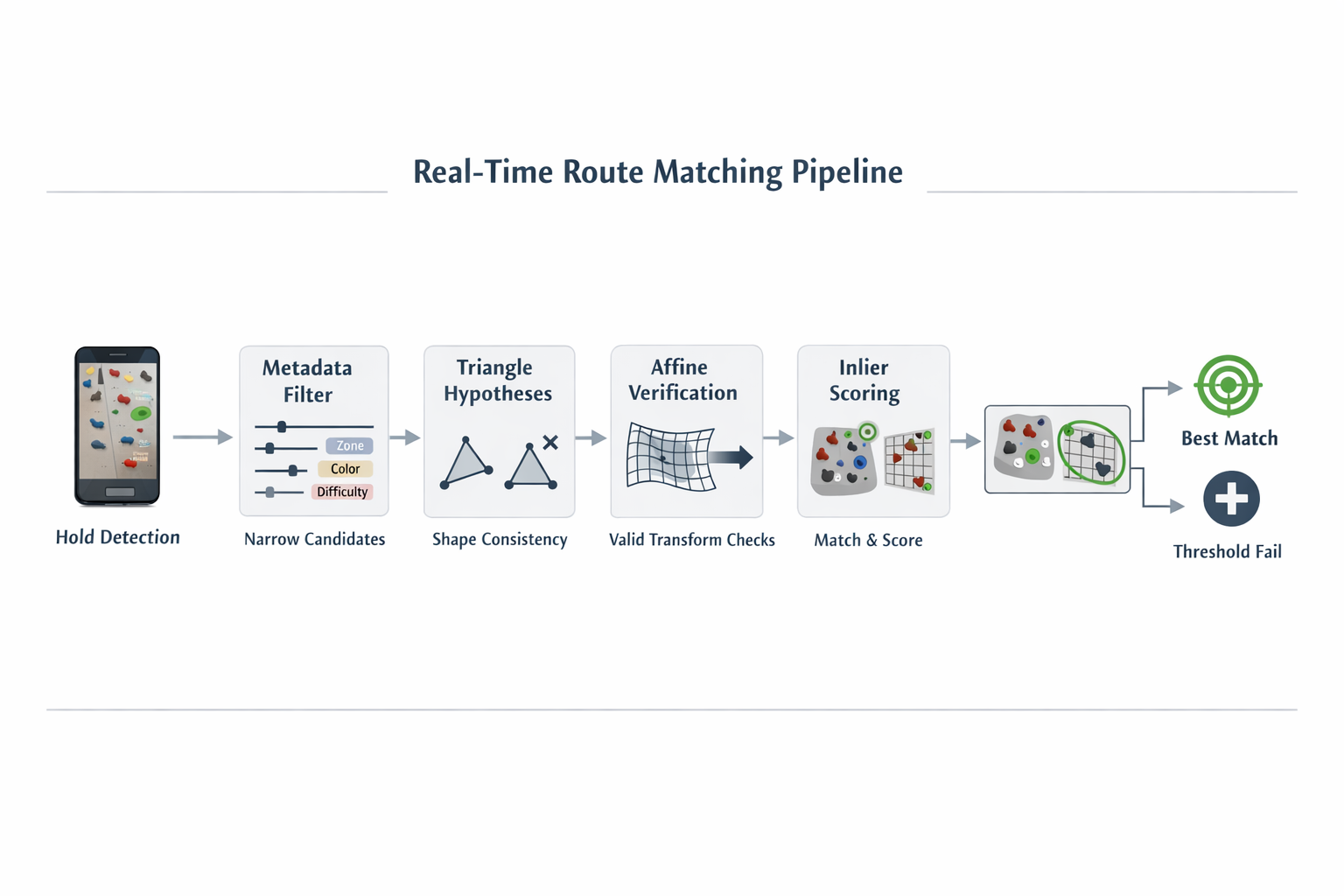

Before doing any heavy geometry, Ascendit first reduces the search space using route metadata. Information like gym, hold color, and difficulty is used to filter candidates down to a small, relevant subset of projects. This keeps the system scalable even in large gyms and avoids comparing every scan to every route on the wall.

Once the candidate set is filtered, the system switches to geometric matching.

For each scan–candidate pair, Ascendit generates affine transform hypotheses from small sets of hold correspondences, similar in spirit to RANSAC-style methods. In practice, this means building hypotheses from triples of holds and checking whether their triangle shapes are consistent after accounting for scale and mild perspective distortion.

When a triangle passes this shape-consistency check, an affine transform is estimated and aggressively filtered. Transforms that introduce mirroring, extreme scaling, heavy skew, or large rotations are rejected outright. This reflects a physical constraint of climbing walls: routes may be photographed from different angles, but they are still rigid surfaces, not flexible objects.

Only transforms that look physically plausible are used for verification.

Under each surviving transform, all detected holds from the scan are projected into the candidate route’s coordinate space. The system then searches for inliers: holds that land close enough to existing route holds and have roughly consistent sizes. Potential matches are resolved into one-to-one correspondences so that a single hold cannot explain multiple detections.

From there, a confidence score is computed using a Jaccard-style ratio between matched and total holds. This favors matches that explain a large portion of both the scan and the candidate route, rather than just finding a few coincidental overlaps.

The final step is an open-set decision.

If no candidate reaches a confidence threshold, Ascendit treats the scan as a new project and creates a new route entry instead of forcing an incorrect match. The threshold itself adapts based on how many holds are visible in the scan: routes with very few holds require much stricter agreement, while denser routes allow for more tolerance to missing detections.

This is important in real gym conditions. Climbers take photos from the side, from below, sometimes with people blocking parts of the wall, and often without capturing the full route. The system has to assume imperfect input and still avoid corrupting the shared dataset with bad matches.

All of this matching happens asynchronously.

Scans are accepted immediately by the backend and queued for processing so the app never blocks on heavy computation. This allows multiple climbers to upload at the same time without slowing down the experience on the wall. Once matching completes, the scan is linked to an existing project or becomes the seed of a new one, and the shared project page updates in real time as others contribute.

On the mobile side, everything is designed around minimizing friction. Scanning a wall should feel faster than navigating menus. Confirming a route should take seconds, not minutes. Logging needs to fit naturally into the flow of a climbing session, not become something you postpone until later.

That low-friction design is what makes community-driven route tracking viable. If logging is slow or tedious, people stop contributing and the data quickly becomes stale. Every part of Ascendit’s pipeline — from camera capture to geometric verification — is built around keeping that moment between finishing a climb and saving it as short as possible.

What emerges from this system is more than personal progress tracking. Ascendit also captures the life cycle of routes themselves: when they first appear, how many climbers attempt them, when they get verified, and how long they remain active on the wall. Over time, this creates a living map of each gym that reflects real climbing behavior, not just setter intent.

Building this has meant blending mobile UX, computer vision, and backend systems into a single product that feels simple on the surface. Most users never see the geometric filtering, transform constraints, or inlier scoring — and that’s exactly the point. The complexity stays behind the scenes so climbers can stay focused on climbing.

And the system is still evolving.

As more climbers and gyms use Ascendit, matching models improve, confidence signals get stronger, and route data becomes richer. What started as a way to log personal projects is becoming a real-time map of climbing activity, shaped entirely by the people on the wall.

Because in a sport where the environment is always changing, the most reliable source of truth will always be the climbers themselves — and the technology has to be built to keep up with them.